"I seem to have loved you in numberless forms, numberless times… In life after life, in age after age, forever. My spellbound heart has made and remade the necklace of songs, That you take as a gift, wear round your neck in your many forms, In life after life, in age after age, forever."

– From Unending Love by Rabindranath Tagore

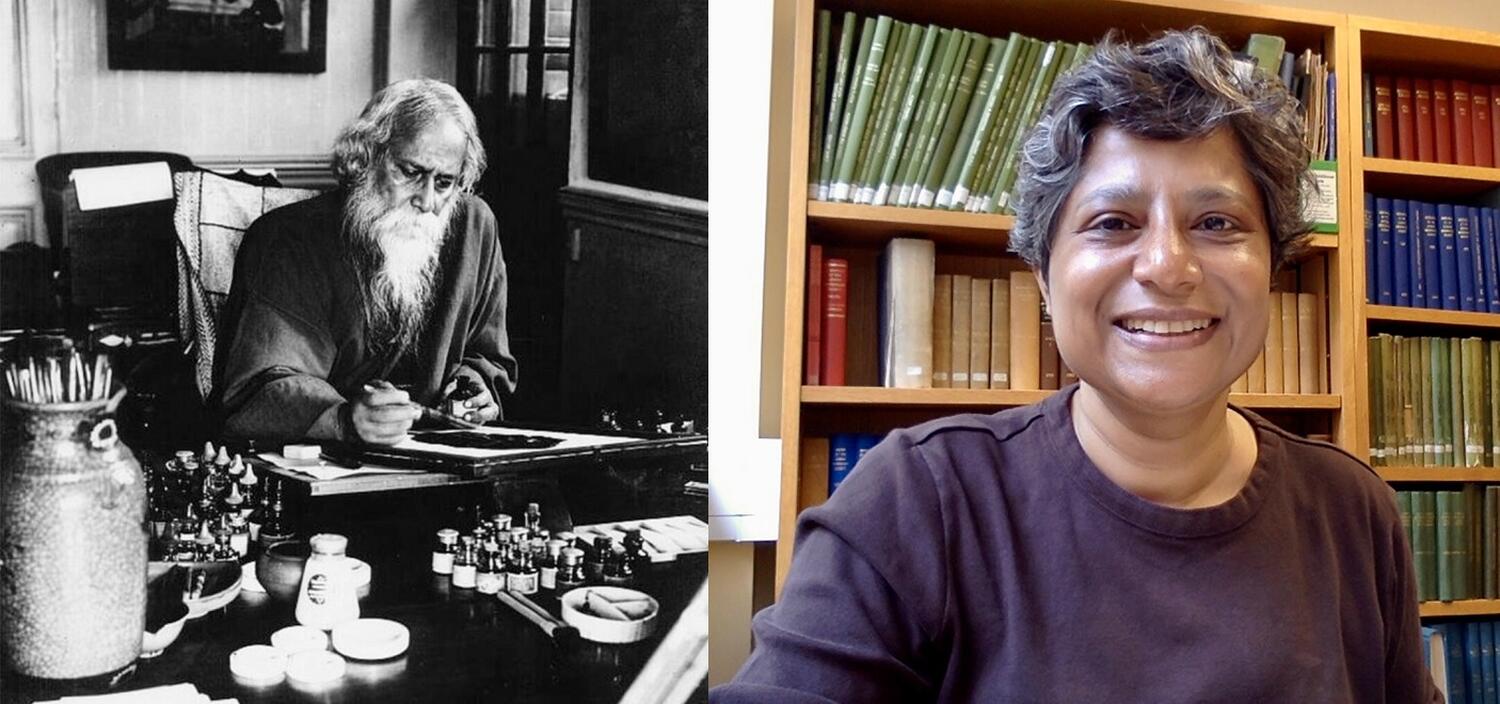

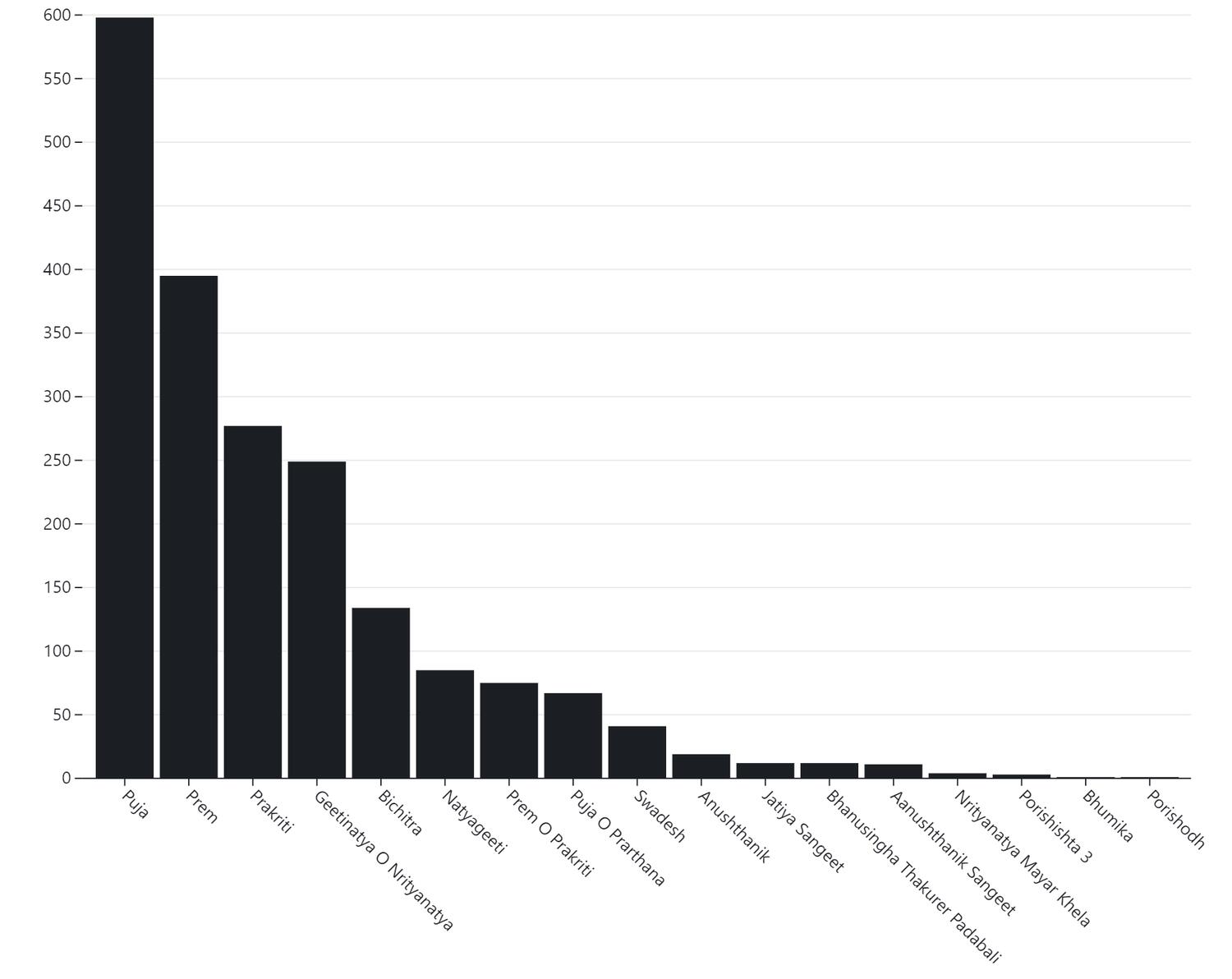

Bengali polymath Rabindranath Tagore wrote thousands of songs. Tagore was not only prolific; he was exceptional. He won the 1913 Nobel Prize in literature, and he was the first Indian and the first non-European to do so. His work was so influential that two of his songs became national anthems. India’s “Jana Gana Mana” and Bangladesh’s “Amar Shonar Bangla” are both Tagore compositions. The Sri Lankan national anthem was also inspired by Tagore’s work. When he oversaw the publication of his corpus of songs (under the title Gitabitan, meaning ‘garden of songs’), he divided his songs into categories and sub-categories. He was fond of writing about seasons, so there are odes to winter, spring, summer and fall, but there are also hundreds of love songs and devotional songs. NCSA affiliate, Rini Mehta, is an associate professor of comparative literature and religion at the University of Illinois in Urbana-Champaign. In a fascinating research project, she’s using Tagore’s songs to teach computers to recognize the concept of love.

Using Music to Learn to Communicate

Using music to cross language barriers might seem unorthodox, but it’s not that unusual. Perhaps one of the most famous examples is the Voyager spacecraft launched in 1977. Highly regarded astronomer Carl Sagan chaired the committee to select music and sounds to be etched onto a golden record and included on board the spacecraft. The audio included a variety of music, both classical and modern, from around the world. These songs were part of a collection of greetings, and for Carl Sagan, just as important to include as the mathematical equations and images of DNA structures.

"There is much more to human beings than perceiving and thinking. We are feeling creatures. However, our emotional life is more difficult to communicate, particularly to beings of very different biological make-up."

Carl Sagan, “Murmurs of Earth: the Voyager Interstellar Record,” 1978, p 13.

Songs and music are often the distillation of a feeling, boiling down language to a core message that can be conveyed in minutes with very little extraneous language to add context. Songs like Tagore’s create a complex canvas of expression that represents humanity’s less tangible features. Teaching computers how to interpret songs, while tricky, might help researchers understand how computers make meaningful connections between words and concepts, particularly since songs use words sparingly to convey a message.

Mehta’s research has a purpose outside her curiosity about how computers understand human language. Computers have the capacity to do many tasks far faster than humans. Computers that understand natural language queries could aid us in far-reaching ways. The potential impact of having a natural conversation with a computer can only be guessed. The internet changed the world in fundamental ways that were both expected and surprising. Creating a computer that can communicate and think like a human would do the same.

“Working more on language processing will open up the world of programming to humanities scholars, and vice versa,” Mehta says. “Computer scientists use input from humanities scholars on the nuances of the figurative use of language. The quality of training is everything, and programs training on millions of tweets or even Wikipedia entries is not sufficient.”

We can already see some challenges Mehta speaks of with the ChatGPT project. ChatGPT is an AI-powered chatbot that uses deep learning to generate natural language responses to questions posed to it by users. Training machines in natural language is tricky, as evidenced by the flurry of articles discussing the problems of bias, inaccuracy and lack of nuance that has come out on the heels of ChatGPT’s rise. Work like Mehta’s may become important as computer scientists face these challenges. Understanding why a machine determines the concepts of a text may help build better natural language processing programs.

Using Natural Language Processing to Interpret Songs

Training a computer to speak and understand human language takes time. To learn a language, the computer must be taught what concepts words represent and how those words are used to form complete thoughts. This is called Natural Language Processing (NLP). NLP uses sophisticated artificial intelligence that stems from combining two disciplines, computer science and linguistics.

NLP is more than simply teaching a computer how to use and understand words. Dictionaries can be uploaded that help a computer associate words with their meanings easily enough. But words aren’t always used in expected ways, with elements like slang, regional meanings and subtle metaphors tripping up a computer with a strict set of interpretive guidelines. A lifetime of speaking has taught us all how to break down what someone says and identify the important pieces of a sentence to get at the intended meaning. Computers need to learn this just as much as humans do, and that’s what NLP does.

In essence, NLP is training computers to converse with humans in the way that we naturally speak.

Songs are a great example of how tricky language can be to interpret. Songs often use symbolism and metaphor to create a mood or share a feeling. While humans might understand what it means when someone “gets under their skin,” these idioms don’t translate well across language barriers. Interpreting the creative use of language isn’t always easy. In the case of Tagore’s songs, it helps that his writings have already been categorized, making his collections of songs an ideal way to teach a computer the nuances of the language of love through song.

Mehta has been feeding Tagore songs into an NLP program that interprets human language. For her research, she’s asked the computer to define the songs that fall under several categories, the main one being love. The results have been fascinating.

To add to the project’s complexity, the songs are fed into the computer in a romanized version of Bengali, the language in which Tagore worked. Most NLP datasets are in English, making training the computer on how to interpret Tagore songs more difficult. However, there is an unexpected upside to working with text written in Bengali.

Once the project began to take shape, Mehta knew she’d need someone experienced with deep learning and NLP, so she reached out to a graduate research assistant from the school of computer science at UIUC.

Tom Reichel knows much about machine learning and working with supercomputing resources, but he doesn’t speak Bengali. This meant he couldn’t be influenced by his interpretation of the songs when he created the methodology to train the NLP to read the meaning in the Tagore songs.

"My inability to read the subject matter of this study strengthens my methodology. In order to validate my work, I have no recourse but to use tests and metrics beyond my subjective interpretation. If I could judge the output myself, the apparent correctness or incorrectness of the results, as I apprehend it, could sway experimental design."

Tom Reichel, graduate research assistant, The Grainger College of Engineering, computer science

Creating a Modern Rosetta Stone with Tagore Songs

Bengali is the fifth most spoken language in the world. Hence, there is value in training computers how to read and interpret the Bengali language. “The volume of data one can procure and one’s ability to process that data are primary limiting factors for success [in NLP],” Reichel says. “We’re interested in gathering a Bengali language dataset large enough to overcome the former limitation and reproduce some of the exciting results we’re largely seeing in English, for which datasets are more prevalent.”

There is also a personal interest that led Mehta to use Tagore songs in her NLP work. Tagore has connections to UIUC, visiting here and impacting the local area. Tagore festivals are still held in Urbana, celebrating the life of the famous poet and songwriter. Mehta has written extensively about Tagore’s place in Champaign-Urbana.

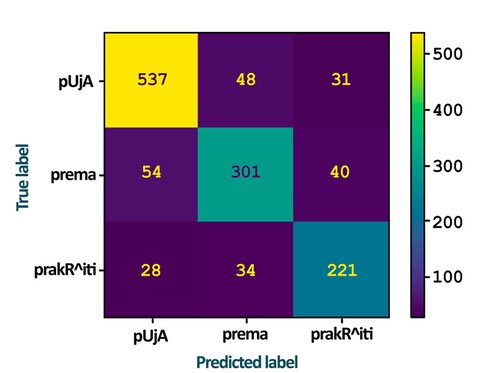

Mehta has hopes beyond teaching computers how to interpret love in a song. The next phase of her project will attempt to teach humans how computers see love. An interesting result occurred as she continued her research. The computer doesn’t always agree with humans about what love is. Sometimes it sees love in songs about spring. Sometimes it doesn’t see love in songs clearly labeled as such. Mehta doesn’t think these are necessarily mistakes in the NLP but rather a difference of interpretation. Much like how two people can read a passage and take away different meanings, Mehta is discovering that computers can do this, too.

“So far, we have used naive Bayes classification,” says Mehta, “and have just let the machine decide from the pattern and occurrence of words in the songs. It would be interesting to move on to our next stage, which is to compare the machine’s choices with other humans. We plan on sending blind samples of songs to Bengali speakers and recording their choices.”

Learning about a new culture often goes both ways. Through Mehta’s work, we’re learning how a computer sees love, but in doing so, we may also be learning a new perspective on Tagore’s work ourselves. Mehta is curious to see if the computer can teach us to see love in a new light.

"This project is not about training the computer to guess a song’s classification correctly. After all, we are comparing the machine’s interpretation with the poet’s. What this project can do is go deep into the corpus of one poet and find an inherent pattern in that corpus. How much of Tagore’s classification is subjective? Since Tagore was a prolific author in the Bengali language for over six decades, his songs can offer insights into the poetic usage of Bengali during those decades. Once those insights are shared with literary scholars, entirely new questions and directions may emerge on where such analyses can lead."

Rini Mehta, comparative literature and religion professor, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Learning how to better understand one another and communicate more effectively could help in several important ways. Major disagreements can stem from miscommunication. Theoretically, understanding why something was communicated badly using a computer as a mediator – a neutral party designed specifically to aid with such things – could resolve potential conflict. Being able to effectively communicate ideas and research through language barriers could aid in scientific breakthroughs. All the potential benefits of learning to communicate with computers likely haven’t even been considered yet.

Exploring these types of ideas is why NCSA supports research like Mehta’s. “NCSA knows which way the wind is blowing and continues to invest in computing resources that can help with the [limitations in processing data] (e.g., Delta, vForge, HAL),” Tom Reichel says. “Access to GPUs with high amounts of vRAM is crucial to training models closer to the state of the art, since they can now vastly exceed the memory specifications of a single GPU on the HAL cluster, and could help us obtain more interesting results once a dataset is assembled.”

The poem at the beginning of this piece was a favorite of Audrey Hepburn’s. Gregory Peck read it at her memorial. Tagore’s work has left an indelible mark on many, writing of love so clearly and elegantly that his songs live on and are still cherished today. Perhaps in time, through Tagore’s words, computers will understand love as we do, as a fundamental part of being human.

Megan Meave Johnson

Editor's note: This story first appeared on the National Center for Supercomputing Applications (NCSA) website.